-

“Just a Number” The War Memoirs of 202101 Acting Corporal James Killikelly

James Killikelly, or Uncle Jimmy as I knew him, was a quiet, kind and modest man. He was, in fact, my Great Uncle, and he lived just a few doors down from my Grandmother in the sleepy town of Ottery St. Mary, in the rural county of East Devon. Jimmy had retired to South West England after a long career in teaching, latterly as the Headmaster of a Roman Catholic primary school in Liverpool. He was evidently loved by his pupils, one of whom, Gerry Marsden, went on to become the lead singer of the ‘Mersey Beat’ group Gerry and the Pacemakers. In an interview with the Liverpool Echo for an article entitled ‘A show of faith in city’s heroes’, published in 2004, he described Jimmy as “a wonderful Christian man”. Another of Jimmy’s former pupils was the actor Michael Angelis who went on to have a career in television, appearing in programmes such as Alan Bleasdale’s ‘Boys from the Blackstuff’ and the BBC comedy series ‘The Liver Birds’. Jimmy, in recognition of his long teaching career at Our Lady of Mount Carmel School and for his service to the Roman Catholic Church was awarded the Benemerenti medal by Pope John XXIII.

I don’t have very many memories of Jimmy, as he died when I was just 10 years old. Now, many years later, I wish that I had had the opportunity to get to know him better, for he had lived a fascinating life. As far as I can ascertain, Jimmy’s memoirs were written when he was in his 70s, on a manual typewriter, and cover a time period from his first days at school (Jimmy attended from the age of 3), through his military service during the First World War, and his post-war teaching career. I came by his memoirs courtesy of my godfather, who is Jimmy’s nephew, as I had started to research another Great Uncle of mine, Jimmy’s younger brother, Gerald. Gerald had been killed in action during the First World War while serving with the Royal Irish Regiment in France. Gerald’s story interested me, as I have childhood memories of my Grandmother, who would often talk fondly, but also with great sadness, for her brother who died aged just 19 years old.

My research into Gerald’s life, and untimely death, yielded precious little information. Gerald is mentioned only briefly in Jimmy’s memoir, in just one single paragraph. Because of this, my attention was diverted away to other potential sources of information, and my research culminated in an emotional visit to a small and lonely cemetery, Arnèke, near Dunkirk where Gerald rests with some of his comrades. What little I was able to discover about Gerald, fills only a page of A4 paper. In an age of social media, where so much of our lives today, however dreary, is well documented, the fact that so many aspects of Gerald’s existence had either not been recorded, or had not survived the passing of time, frustrated me.

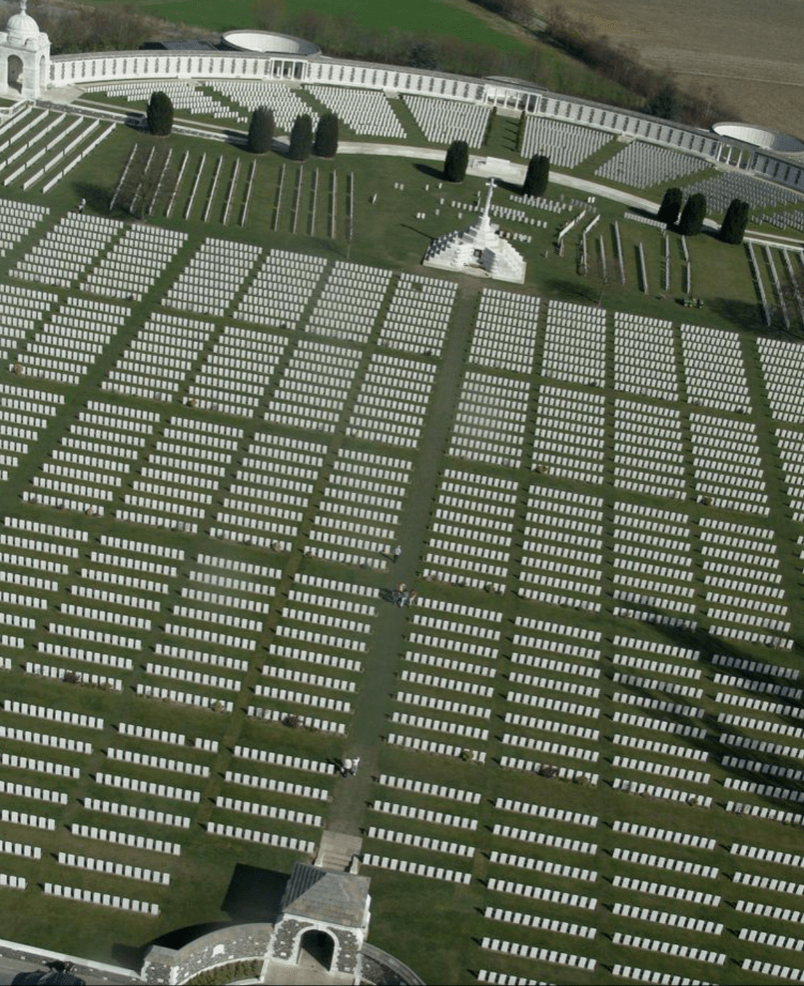

It is with some degree of shame then, that I must admit to having paid little more than scant attention to Jimmy’s memoir until relatively recently. I had always intended to convert Jimmy’s type-written manuscript to an electronic format, with a view, maybe, to some form of publication. I made a start with it in the early to mid-2000s. But, life, as they say, gets in the way, and the pages languished for several more years, in a cupboard in my parents house. In the latter half of 2019 I made the decision to pick this project back up again and edit the manuscript properly. To say that I hadn’t previously given Jimmy’s memoirs the attention they deserved, is more than an understatement. His experiences, of such events as Zeppelins bombing the theatre district of London, to life, and death on the Western Front, of Ypres and Passchendaele, is worthy of being more widely read and appreciated. I made the decision to only focus on Jimmy’s wartime service because I felt strongly that his experiences as a young soldier and signaller during the‘War to end all Wars’ are of historical significance. I hope that I’ve done Jimmy’s book justice. I am sure that his writings were a labour of love for him in his later years. In my later life, editing them became the same for me.

In editing this book, I have attempted, here and there, to give some wider historical context to Jimmy’s story and, where it is relevant, provide the reader with some more information about the places and battles to which he refers. My intention was not to distract, I wanted Jimmy to speak for himself, and for my words to merely complement his, hopefully I got the balance right.

Martin Laycock, Surrey, August 2022.

My Great Uncle – James Killikelly My War – Part One.

St. Mary’s College, Hammersmith.

My old Headmaster, H.J. Morgan, prior to my entrance into St. Mary’s Training College, wished me well, and told me that I should find my two years stay in ‘Simmaries’ probably the happiest two years of my life.

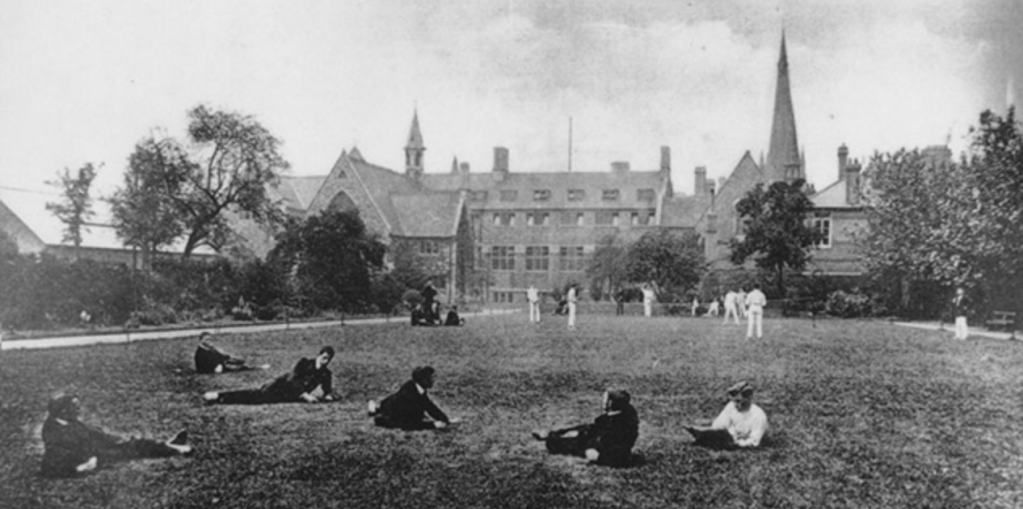

Students at the St. Mary’s campus in Hammersmith during the 1850s. I was never in a position to judge how exact was his prophecy, for my first year at College coincided with the beginning of the 1914-18 war. As young men in civilian clothes, some just under, and some of military age, it behoved us, therefore, to be careful not to inflict ourselves publicly on the general population, at a time when posters proclaimed the fact that our King and Country needed us. Our main place of enjoyment was confined to the indoors, though we did play whatever football we could with the other London Colleges. On occasions we showed that we took the country’s situation seriously, by a series of route marches though what good that did us, I never really found out.

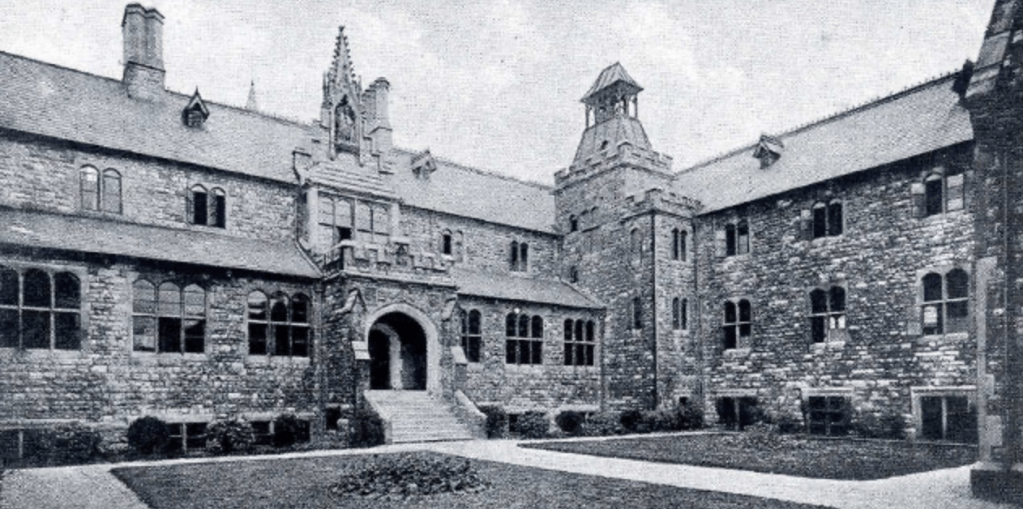

The Quadrangle at the St. Mary’s campus in Hammersmith in the 1850s. Towards the close of my first year, the Board of Education issued a statement that men in training colleges could enlist, and a Teachers’ Certificate would be granted after a two year probationary period following demobilisation. This pronouncement was an important one, as it meant security in our profession, if we were lucky enough to survive the war, no further study, and no examination. Naturally, we had many discussions amongst ourselves as to what we should do.

One day a friend of mine, Tom Hartney, said he had made up his mind, and was going to join the army immediately the Summer term was over. Together we looked through a newspaper which listed the names of all the British Regiments. Tom’s finger pointed to one, and he said “Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry, that sounds a fine lot – I think I’ll join them”.

1/4 Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry cap badge. Summer vacation over, I returned to London to begin my second year’s training. A letter from a place called Bicester informed me that Tom had kept his word, and was now one of His Majesty’s Forces. One weekend he came to visit us at the college, and, full of enthusiasm, he invited me to join him. I agreed, and he promised to send me a railway voucher to enable me to travel to Oxford. When this arrived I summoned up courage to ask for an interview with the Principal. When I told him I wanted to join the army, he refused to let me go. I said that the Board had given us permission to join and had guaranteed our Certificate. He relented somewhat, and then said that my parents must write to him to say that I had their permission to join up. I didn’t fancy this very much, but concocted a letter saying that the Principal had given me permission to join the army, but as a matter of form, he wanted their permission as well.

When their reply was about due, I went to the porter at the Lodge, and showed him my father’s writing, and asked him had a letter come for the Principal in this hand. He said it had, and very shortly afterwards I was knocking at the Prinny’s door. He seemed taken back to see me so soon, but agreed he had received a letter from my father giving me permission. “Can I go then?”, I asked. “Where are you going to?” he said. “Oxford” I replied. “How are you going to get there?”. I said I had a railway warrant, so he gave in, and that evening I had my medical examination, and was accepted as a member of the 3/4 Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry. The doctor seemed to have some doubts about my age, as I looked much younger than I was. I told him truthfully I was 19, and he took my word that I was. Just at this time, there was a movement, emptying out those boys of 15 and upwards, who had given false ages to join the army.

Oxford.

Tom Hartney had met me at the station, and had taken me to Battalion Headquarters. After I had received the ‘King’s Shilling’ (there wasn’t one really) a quartermaster sergeant issued me with two lots of uniform, a cap and badge, shoulder badges, a pair of boots and socks. These I stowed inside a huge rucksack, and together with my suitcase we proceeded to Tom’s billet. I found out later that Tom had pulled some strings to get me there, for I had been allotted to C Company who were billeted on the other side of the city, close to the railway station. Tom was in A Company, and he was living with four others in a small house in a street off the Iffley Road.

Here, then, I spent the next few months, sharing a bed with Tom, while the other four lads slept on mattresses on the floor of the back bedroom. In some respects I was lucky to find myself in this billet, for besides being with Tom, I gained an immense amount of useful information about how to conduct myself as a soldier, from these ‘old sweats’ of a few months experience. One big drawback was that when C Coy. was lined up as a company, I had to travel across the city to Beaumont Street to take my place on parade, and that meant leaving earlier than the others to make sure I was on time. Fortunately the ‘rookies’ parade took place in the parks at the back of Magdalen College, and, as most of the battalion paraded there, I was able to leave with the others.

I found how useful these ‘old’ soldiers in my billet were, when I arrived back in there, after one parade with a complete kit, consisting of belt, haversack, straps, water bottle, entrenching tool, handle, small haversack, bayonet frog, and the rest. The belt and straps were leather and had all kinds of buckles and straps to which the rest of the paraphernalia had to be attached. The boys gladly showed me all the tricks of the trade, how to fold my greatcoat, and put it in the pack so it was absolutely square, and how to arrange everything so that I felt ‘comfortable’ when I fastened it all about my body. They gave me tips on cleaning buttons, boots, polishing the leather, fastening my puttees, and thus saved me any trouble I might have been in, when inspected by an officer on parade.

We lived with a Mr. and Mrs. Bossom, and on the whole, I suppose, we could have fared worse. The food was immeasurably superior to the terrible meals we got at Simmaries. One meal I always found strange, a bottle of beer and bread and cheese, and, as I didn’t like beer at that time, naturally I never looked forward to this dinner with any relish. Mrs. Bossom was a woman of uncertain age probably in the early thirties, and she was not averse to the high spirited rough play of the four young soldiers, though she always reproved them when they tried to go too far. Mr. Bossom we only saw at weekends, and usually discovered him on his hands and knees, scrubbing the floor or polishing the furniture, and doing the washing. Mrs. Bossom certainly wore the trousers as far as he was concerned. I always associate the song ‘Little Brown Jug’ with Mrs. Bossom on the occasion she invited me to play the piano in the front room. It was many years afterwards when I discovered the reason why, for I was too innocent in those days.

I used to enjoy the rookies’ drill in the parks and tried my best to be a smart soldier. One morning when we were doing rifle drill, an officer approached the squad, and asked the drill sergeant if he could speak to me. I was told to fall out, and it was an embarrassed rookie who presented himself to the officer, for I didn’t know what to do with my rifle or myself. To my astonishment, this officer said he had heard I could play football. He asked me various questions about the teams I had played for, and then told me I had been selected to play for the battalion on the following Saturday. I suspected Tom Hartney had been at work somehow, but he never mentioned it to me, and did not give me any satisfaction when I told him what had happened. Somehow I didn’t feel at all nervous when I turned out on the Saturday, and I suppose I must have satisfied Captain Wallace, an Oxford half-blue, for I kept my place in the side for the rest of my stay in England. I often wondered why on earth he had taken such a chance with a young unknown player. Before I left Oxford, I had the pleasure of playing on the Oxford City ground and the University ground in Iffley Road.

On wet days when it was too bad to do our drills in the park, we were taken indoors and given lectures by two regular sergeants, who had been too old to go out to France with the 1st and 2nd Battalions. While the rain was pouring down we would be given lectures on the history of the regiment, with emphasis on wonderful deeds performed in the Peninsular War, and with Wolfe in Canada. Thus we were imbued with pride in the 43rd and 52nd Foot, and learnt to rattle off quotations such as ‘lightest of line and fleetest of foot, never been surpassed in arms since arms were first borne by men’. We also learned that the two gold braids on the collars of the officers’ uniforms indicated how the regiment pulled the Guards through at the battle of Waterloo. With all this in our minds, we determined to be worthy successors to these wonderful men, and we strutted and marched through the streets with our heads up high.

Each week we had a route march through the country round Oxford. On this day I was up especially early to parade and be inspected in Beaumont Street prior to moving off to join the rest of the battalion lined up before Colonel Stockton in Broad Street. Here the Colonel mounted his horse with the same dog beside him on every occasion, and would call us to attention – ‘Oxfordshires Shun’ etc. A shiver always went up my back when I heard his order ‘Oxfordshires’. Away then we would march, rifles at the ‘trail’, until we got the order, ‘March at ease’, when rifles were slung and songs were sung. Two things always remain in my mind – firstly, the number of dogs that came with us on these marches, and secondly, the way cows behaved as we approached the field they were in. As we drew near, the whole herd came to the gate, and stood staring at us, and then rushed to the back of the field before they came back to the road at the other end of the field, to bid us goodbye. The colonel’s dog disappeared at the end of each march, to reappear the following week standing by his horse in Broad Street.

Christmas came, and shortly afterwards my first inoculation. This was a very painful affair, and we were excused duty for twenty-four hours. My first leave followed, and I went up home to Liverpool to impress everyone with my smartness of step at 140 to the minute. When I returned to Oxford, I learned that we were to leave in a few days for an unknown destination. Before that happened, I had to have my second inoculation, and as this came on the day before we left, I found I had to carry a full pack and kitbag to the railway station, with my body aching from the effects of the second jab. While the train was in motion we looked out for the names of stations we passed, and thus discovered we were going west. Finally we came to a stop at Weston Super Mare, where we were to receive more recruits, and train as a supply battalion to the 1/4th and 2/4th battalions, who had been out in France for nearly twelve months.

Weston-super-Mare.

It was a pleasant surprise to find our new quarters were to be at this charming seaside resort. Luck was with me, when I found myself billeted in a terraced house with a Lance Corporal Powell of A Company, as my fellow lodger. Our hosts were a middle-aged childless couple, and I found conditions with them infinitely superior to those I had in Oxford. A sitting room was placed at our disposal, and here, too, we had our meals served, with the exception of Sunday dinner and tea, which we took with our good hosts, whose name I regret to say I forget. This was a very comfortable home, and I counted myself very fortunate in being allotted to it.

One day I found my name on orders with instructions to report to the signal section. Again I suspected the hand of Tom Hartney behind this, for he had already joined the section, and boasted one stripe on each arm. In command of the signal section was Lieutenant Stevenson, whom I grew to respect and admire as the months went by. He was a professor (of History I think) at Oxford University, and he brought his charm and erudition into the army, where one had got used to barks and commands. Under him was Sgt. Perkins (Polly) who had been wounded in France and hoped he had seen the last of active service by becoming a signalling instructor. He was very fair, and very competent, but always kept a sufficiently respectable distance between himself and his men. I loved this side of my army service, and on the whole, the signals became a happy little family. Lieutenant Stevenson used to take the theoretical side of our instruction using a book called Training Manual of Signalling, T.M.S., which he always called ‘Toc Emma Esses’, and so we came to call him ‘Old Toc Emma Esses’.

Every morning we did our PT on the grass lawns by the promenade. When we had a short break, most of the boys used to rush down to the water’s edge, and stare in rapture at the scene in front of them. Prior to going to Weston, the majority had never seen the sea. These days on the green lawns at the seaside were ideal, and as far as I can remember, we seem to have been blessed with good weather all the time we were at Weston-super-Mare.

The football team was beaten in the first round of a cup competition soon after our arrival in the town, and enthusiasm for a battalion team seemed to be lacking, so for the rest of our stay, no further attempt was made to arrange any inter-battalion matches. By a stroke of good fortune, the secretary of the town team lived in the street where a number of us were billeted. Three of us were invited to become members of his side, and so while the battalion remained in Weston, we played each Saturday when they had a fixture, for Saturday afternoon was always a free half day.

On one occasion we were due to play Bristol University in Bristol and arrangements had been made to travel there and back by coach. So that we would have time to spend the evening in Bristol, the three of us applied for, and received permission to remain out until 10.30 ‘to attend a party’. On Friday evening the battalion buglers went round the town sounding the ‘Alarm’, calling all men to parade at the usual parade grounds. Cinemas were entered and soldiers were summoned by a notice on the screen to leave at once. As far as we could make out, reports had been received of a possible German landing on the east coast, and troops were alerted to be ready to move at a moments notice. After the parades had been inspected, we were dismissed and told to remain in our billets until further orders. Early on Saturday morning a sergeant knocked at each door in our district, ordering everyone to remain in his billet. Nothing further happened during the morning, and we three members of the football team called at the secretary’s house and told him the news. He asked us if we were willing to risk leaving the town and go to Bristol, and when we told him we were (for most of us by this time thought the alarm was only a ‘scare’), he said he would arrange to have the bus brought to the back of our billets, so we could leave by the back door.

Everything went smoothly and we went to Bristol and won 5-3. After the game we had a meal in the city, and then visited the Bristol Hippodrome for the evening’s entertainment. Thus when we got back to Weston, it was after midnight – too late to hand in our passes, even if we had dared to do so – and so we skulked into our digs, and were relieved at any rate to find our fellow soldiers asleep in their beds. On the following morning, Sunday, my two football companions handed in their passes to the orderly corporal at their church parade. I, of course, attended the catholic church, and had no opportunity of getting rid of mine, and wondered what I should do.

I went round to see ‘Orders’ that night – these were posted in convenient places close to the billets – and to my horror saw my name in seemingly large letters, ordering me to report to the Battalion Orderly Room on Monday morning. All I could think of was that our escapade had been discovered, but I was the only one to be found out. Sleep was impossible that night, for no doubt my crime was one of great seriousness. We had never given it a thought that by the time we had got back from Bristol, the battalion could have been on its way to Norfolk or Suffolk, and we three left stranded in Weston, and written down as deserters.

With great trepidation, therefore, I duly presented myself at Headquarters on that Monday morning. When I was bidden to enter, I noticed that the R.S.M. was quite cheerful and actually smiled at me. My spirits rose at once – it didn’t seem as if my head was ready for the block yet awhile, “I notice” said the R.S.M. “that you haven’t done your live firing musketry course. There is a party going up to Kidderminster to-day, and I want you to join it. Go back to your billet and get yourself ready to report in full marching order here at 10.30”. I could hardly get out of the room quickly enough, but I remembered that late pass I had not given up on Saturday night, and I said as calmly as I could, “Oh sir, I was not able to hand my pass in on Saturday”. “Throw it on the table” said the R.S.M. “Yes sir, thank you sir” and out I went into the fresh morning Somerset air.

When I came to my senses, and thought what was in store for me in the next fortnight, I didn’t feel exactly at ease as I might have done. Although I had done rifle drill – ‘slope arms, present arms, trail arms, shoulder arms, etc.’, I didn’t know one end of the rifle from the other, and wondered how I could make up for my ignorance, before trying to put a bullet into a target. On arriving at Kidderminster, we marched to the camp where the rifle range was situated. Fortunately for me, I found the rest of the party a very friendly lot, and after a time I told them of my predicament. After the training they had received they could understand how I felt, and they proceeded to give me a month’s musketry instruction in a couple of hours. Someone has a clip of dummy bullets, and I practised loading not an easy job at all for a beginner. Then I was told about the foresight and back-sight, how to align them on the target so I was aiming at 6 o’clock on the bull’s eye. I had to pretend to fire and then unload, making sure that no bullets were left in the spout by pushing the bolt backwards and forwards. The finer points of triangle of error wind resistance, distances, were left in abeyance for the time being.

Thus on the morrow, I found myself handling live ammunition, thoroughly scared and praying that everything would go well. Our first shots were fired at targets 100 yards away, and the results were signalled back by men in the butts indicating the success or otherwise of each shot. I remember a bull was shown by a white circle rising slowly until it rested flat on the centre black spot of the target. A complete miss produced a flag waving sideways on the target telling the ‘marksman’ it was a washout. Inners and outers had other signals, and I soon got to know them. I had been told by my amateur instructors to take things slowly, making a first pressure before I actually pulled the trigger, and to hold the rifle well into the shoulder armpit. I was also warned to be prepared for the kick of the rifle into the armpit, as the bullet left the rifle.

Things went better than I expected, and at 100 and 200 yards, I found I could do reasonably well. 500 and 600 yards found my weakness and I regretted not having received proper instruction. Worse was to come, however, in the ‘mad minute’. Here we were allowed to load ten cartridges into the chamber, and then to fire as rapidly as possible at the target, ejecting each used cartridge after every shot and shooting the next bullet into the ‘spout’. I managed to get all these ten bullets away, though some of them didn’t hit the target. Then came the job of unloading, and reloading the remaining five, but before I could do this, time was up, and so my effort in the mad minute was a poor one. Further trouble came when we were given moving targets to fire at. I had no idea what the correct procedure was in this case, and although I had a ‘go’, none of my shots hit the small target that bobbed up and down.

Kidderminster was a dull, uninteresting town, and there was little to be done in the free time that was left to us. The fortnight slowly passed away, and I left the firing range with a feeling that I should have done fairly well with proper instruction beforehand. The actual firing itself was very pleasurable, and I was always pleased when further practice came along at varying times during my service. One thing I never liked, however, was the cleaning of the rifle – boiling water had to be used after the firing, and then the cleaning with oily rag, four by two, and pull through. I never seemed to get my gun as clean as the other chaps, and I always dreaded rifle inspection, though strangely enough, I was never pulled up over it.

Back then I came to Weston to enjoy some more football with Ashcombe Rangers without any further qualms. As far as I can remember, we were not defeated in any of the games I played in, and after we had left the town for Salisbury Plain, the secretary came to see us there, bringing silver medals for the three of us – we had won some competition or other – it was a very fine gesture.

So far I have not made mention of church parades. the R.C.’s always paraded on their own, and as there were only some dozen of us at any time, usually the orderly corporal or orderly sergeant for the day would come to inspect us, and then leave us to be marched off by any NCO we had in the ranks, or by the senior serving soldier. At Oxford we lined up at Magdalen Bridge, and went to a church in the Iffley Road, which was very convenient for us living close by. The Catholic Church at Weston was some distance out of the centre of the town, and my memory of our attendance there chiefly concerns seeing two of our officers 2/Lt. Stockton and 2/Lt. Sherrington waiting outside the church to greet two pretty girl members of the congregation each Sunday. 2/Lt. Stockton was the Colonel’s nephew, and 2/Lt. Sherrington, whom I met years after at Battalion dinners, I discovered to be a Liverpool man who played a great part in War 2, organising rail transport. It is worth mentioning perhaps, that on no occasion, at any church, in any town, did the members of the congregation deign to have conversation with us.

Three times I had to see the doctor while I was at Weston. On the first occasion, I had to attend with a number of others to be vaccinated. After vaccination, we were excused all parades for about ten days, though we went for a short walk of half an hour or so each morning, and then retired to our billets to rest for the remainder of the day. Some of the chaps suffered agonies with terribly sore arms, and vied with one another as to whose arm looked the worst. My vaccination did not take, but I still paraded with the squad each morning, and then retired to enjoy the rest of the day. One morning we were told that we should parade next day before the M.O. for inspection. I thought this would be a good time to slip back quietly to the signal section. This I did – nothing was said – and I heard no more from the medical department.

Weston Super Mare had a very fine swimming bath, and I used to go there for a swim whenever I got the chance. During my first year at Hammersmith I became a member of the water polo team, and we trained at the Lime Grove Baths, where there were a series of high diving boards. I once went to the highest board and the distance from the water frightened me. Gradually, however, I worked my way up until I conquered my fears, and got quite a lot of pleasure in being able to dive off the 30ft. board. The bottom of the bath at the point of entry had been deepened so that the water there was 9 ft.6 ins. deep, and this gave quite a good margin before resurfacing. The Weston bath too, had a high board, and one day I decided to try a dive from it. As far as I know, my dive was quite correct, but on entering the water the bottom of the bath seemed to come too quickly up to me, and I hit my head on the tiles. I found out later that the water was only 6 ft.6ins deep at this point. There was a slight moment of feeling dazed, but I recovered, came to the top, swam to the side, and got out. The bath was fairly empty at the time, and no one had seen me go off the board. I quickly got dressed, and went home feeling rather shaky.

My fellow lodger Lance Corporal Powell, happened to be on orderly duty that week and one of his jobs was to take the names of the ‘sick, lame and lazy’ for medical parade later in the morning. I thought I had a good excuse for an extra ‘lie-in’, so I gave him my name that night, and enjoyed the extra hours in bed before seeing the doctor next day. The doctor was very sympathetic when I had told him what I had done, and excused me from duty for the rest of the day. Actually there was little the matter with me.

While we were in Weston we were placed in our different categories from A1 down to C3, to decide how fit we were for overseas service, for by this time we became a draft battalion, and had to be ready to supply the two Territorial battalions in France with men, to make up any loss they sustained. I duly went through all the tests, and was rather intrigued by the remark of the M.O. when he had finished with me.

“You’ve got the constitution of a pig”.

I never knew whether that was a compliment or otherwise. At any rate I was marked A1.

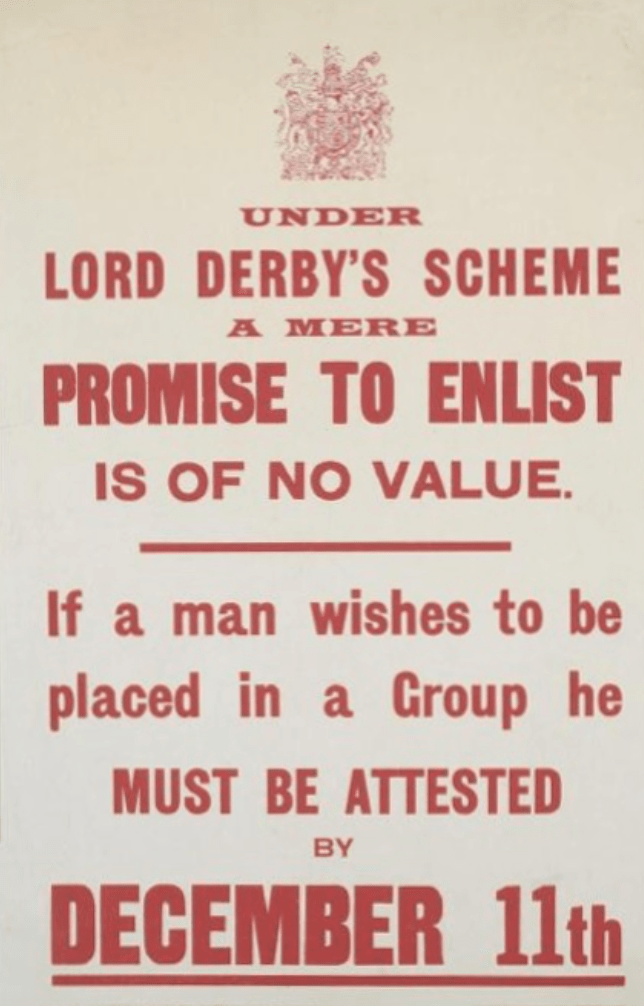

Weston saw a new type of recruit called the Derby men. Lord Derby had devised a scheme whereby men promised to join the army provided that certain circumstances which prevented them volunteering previously were removed. There was a certain amount of ‘eye-wash’ about the scheme, and these men found themselves in the army much sooner than they had anticipated when they completed the forms handed to them. For many years afterwards the Derby group were spoken of in rather derisive terms by those who had volunteered in the early months of the war. The strange thing was, that when conscription came in later on, I never heard any scathing remarks attributed to them, as had been poured upon these volunteers under the Derby scheme. On the whole these Derby soldiers were mature men, much older than the young lads who had rushed to join the colours at the outbreak of war. They were given three months training which was considered sufficient to turn them into competent fighting soldiers.

Edward George Villiers Stanley, 17th Earl of Derby, KG, GCB, GCVO, TD, PC, JP.

1865–1948.It was from Weston then that our first drafts went out to the territorial battalions, to fill in the gaps caused by casualties and illnesses – trench feet was a common complaint in the early days of the war due to waterlogged trenches. Our first draft of Derby recruits sent out, spent only a few days in the line before most of them were either killed or wounded, for they had arrived just at the time when some fierce fighting was taking place on the Somme. The result of these losses was a speeding up of the number of drafts being sent out as the weeks went by.

Derby Scheme poster from November 1915. Salisbury Plain

The winter months went by, and rumour had it that we were due for Salisbury Plain – a rumour that soon proved to be true. The Plain had a bad reputation amongst the rank and file, and so there was no eager anticipation for the future move. With the coming of Spring we found ourselves detraining at a small station which had a larger name of Ludgershall. Except for the station, there didn’t seem much else in Ludgershall so we felt really and truly isolated. The nearest town was Tidworth, and further away still Andover, but there was nothing there to entice us away from the camp. The Plain seemed one mass of army camps as far as the eye could see, and the constant meeting of officers and military police outside our own particular camp, did not encourage us to wander too far.

Soon we became aware what real soldiering meant. We slept on the ground on top of waterproof sheets with a couple of blankets, and our haversack as pillow. Rifles had to be stacked on the tent pole, and our first duty on rising, was to roll up the tent walls, tighten the ropes, fold our blankets in the right number of pleats, and hide every personal possession from view of the orderly officer, who came to inspect every tent on his rounds. Washing and shaving was done in the sheds provided, while the latrines were of the most primitive kind – hidden by canvas sheeting were trenches, in front of which one sat on a wooden pole stretching from one end to the other – there was no privacy of any kind.

Buglers came into their own and we were reminded of our various parades from dawn to dusk. “Get out of bed – – – – – – – -“ began the day – “come to the cookhouse door boys – – – – – -“ “Quarter of an hour to get ready in.” “Fall in A, fall in B- – – – -“, “You can be a defaulter as long as you like, as long as you answer your name”, etc. etc. All these were preceded by the battalion call so that there could be no confusion with calls from other regiments in the neighbourhood. Apart from ‘Jankers’, the most irritating call of all was reveille, for despite having to lie on hard ground we were young enough to get used to discomfort, and hated the early morning call to begin the day. It was said that no one ever became a soldier until he answered the confined to barracks call – this meant reporting to the guard room every hour after parades were over. I was lucky enough to escape this indignity all through my army life, though there were times when I might have deserved such punishment had I been caught – thus I was never able to say I was a real hundred per cent soldier.

As the days got warmer we managed to get in some cricket practice, and I was lucky enough to play in one or two games for the battalion eleven. There were no prepared wickets, and the matches were played on matting. I didn’t perform extraordinarily well, but as I was absent for six weeks during the summer, I never really got accustomed to playing on matting.

It was at this time that I lost the companionship of my friend Tom Hartney. He found himself one day on orders to leave with a draft for France. With his departure I found myself very much alone, though I thought it would not be long before I joined him again in the 1/4th battalion. It was not to be, however, for Tom’s stripe was handed on to me, and shortly afterwards I was detailed to attend an instructors’ signalling course at Weymouth.

At Ludgershall, Tom Hartney used to march the dozen or so R.C’s each Sunday to a YMCA tent some distance away from our camp. In this tent Mass was said, the priest using a piano as an altar, an improvisation which I think had had the effect of making the service more devotional. After Mass we marched back to the camp at ease, an no one took much notice of us. My appointment as a Lance Corporal was on orders on a Saturday night, too late for the stripe to be sewn on for the Sunday parade – nevertheless I automatically took charge of the R.C. contingent and marched them off to the YM tent. After Mass as we strolled back to our camp, we heard the sound of a galloping horse from behind us, and then a strident voice called us to attention. We were berated right, left and centre by this red tabbed officer for our slovenly behaviour, and then he lined us up and sent us on our way in soldierly fashion. I was thankful all this time that my new stripes were not on my tunic, for I am sure he would have had them off, there and then. In future I saw to it that we marched to attention, both going and returning from church.

I have said that Tom’s departure left a sense of loneliness in me, but I never for one moment thought I would not see him again. Somehow any letter he might have written to me from France did not reach me, and so I lost contact with him. When I finally went abroad, I wasn’t able to get a lot of information about him, and someone said he had been wounded and left the battalion. It was some years after the war was over, that I was introduced to a chap who, on hearing my name, asked if I had known a Tom Hartney. He had met him in a convalescent camp at Curragh, in Ireland, and Tom had mentioned me to him as a fellow Liverpudlian. I thought then, that I should try to make contact with Tom, and wrote to the teachers’ association in Hull, asking for his school address. This I obtained, and wrote to him, explaining how I had come across his old time Ireland companion, and felt I should like to hear from him again. Tom wrote back, but to me it wasn’t the same Tom Hartney writing, and it seemed as if he did not wish to renew our old friendship, and so I did not bother him further.

Shortly after coming to the Plain, I passed my test as a first class signaller. Signallers on the whole, were not very popular with the other ranks, for we were excused all fatigues and guard duties, and as these were hated by all soldiers, there was little doubt that those who had to do them, felt that these duties should be shared by all, no matter what class they were under. Guard duties, particularly, were detested, for a most stringent inspection was given to the incoming and outgoing guards, and there were some dozen ways of being hauled over the coals during the twenty four hours of duty. My certificate read as follows –

Signallers Classification Tests

Certified that Pte. 5579 Killikelly J. 4th O.B.L.I. has been examined in accordance with para 207 Training Manual signalling (Provisional) 1915 and the results show he had attained the standard of a 1st Class Signaller.

24th May 1916

Francis A. Mason Capt. R.E. Signalling Officer

A Group 3rd Line South Mid. Div.

Shortly after I had received my first stripe, I was told by Lt. Stevenson that he had recommended me to attend an instructors’ course which was to be held at the Southern Command Signalling School, and was to last for six weeks.

Weymouth.

The signalling school was situated at a camp occupied by the Dorset Regiment at Weymouth, and so one morning I left the Plain, not sorry to find myself near the sea again. The camp was, actually, at Wyke Regis, just outside the town, and we took over

some huts on the outside of the Dorset camp. The school consisted of some hundred signallers who hoped to qualify as instructors at the end of the course, about two thirds being N.C.O’s and one third commissioned officers. In command was a Capt. Allott, supported by his Royal Engineers team of two officers and nine sergeants. We were well housed, and well fed, and I found the trestle beds very comfortable after sleeping on the ground on the Plain.

The derelict former Army camp at Wyke Regis, Dorset taken circa 2010. Work started before breakfast with flag drill and we got plenty of exercise doing this for the order was ‘Three times through the alphabet’ and as the flag poles were thicker and heavier and longer than I’d been used to, there were blisters and tired arms during the first few days. We were taken through all the varieties of signal equipment, buzzer work, lamp reading, disc and shutter sending and receiving, and the use of the heliograph. Lectures were given on the theoretical side in the afternoons, and each night we went out to the cliffs on the English Channel to do more lamp reading. This was a very tricky job, especially if the wind was strong, for our eyes watered, and we couldn’t afford to blink in case we missed a letter, and, as the standard was 98 out of 100, we just simply had to hold on, and let the tears flow.

Signalling Post on the Western Front

Heliograph Each week we had a written examination and the results were published on a board the following day. I had, of course, been brought up on examinations, and thus this part of the course I enjoyed. Although I was never top, I always found my name amongst the first half dozen, and took little pride in it. The mechanical side of our exercises I didn’t enjoy – I was never sure sure of assembling heliographs correctly and speedily, or aligning lamps and telescopes on tripod stands. Special attention was paid to map reading, and I felt pretty confident I could pass any test in that sphere, but I got a rude shock oneway during the last week of our six weeks’ course, when all the final tests were being made.

Sundays were free days, and I can still remember the delight we always had, when we heard the sounds of the church parade of the Dorsets not so far away. As they marched off to church, the band struck up the Dorset march past – “Oh it’s nice to get up in the morning but it’s better to lie in bed”. We thoroughly enjoyed our extra lie in bed. Later on I went into Weymouth to attend a late Mass on my own.

When our last week arrived we were given tests in sending and receiving in the various methods of signalling. Everything was in code, so there was no chance of guesswork. The instructors were the operators when we read the code messages, and were the receivers when we sent them. One very ticklish job was to discover a man waving a blue flag against a dark background, by means of a telescope, and then to send him a message on a heliograph, after assembling the instrument and aligning it on him. This had to be done in a certain time, and I was very thankful indeed when everything went well for me, and I knew I had been successful. We had to use the helio both with the sun in front of us, and also at the rear. Two mirrors had to be used in the latter case, and of course, it was a bit more tricky.

On another day we were given a map and a bicycle, and told to deliver about half a dozen messages to certain positions marked on the map. I felt very confident about this test, but found myself in trouble right at the start. According to my map I had to take the first road on the left after leaving the camp, but as I progressed, there didn’t seem to be any turning, so after cycling for some distance, I concluded that I had missed it, and returned to make a closer scrutiny of the road. I had noticed a very narrow opening previously, but didn’t for one moment consider it was of sufficient importance to be marked on the map as a road. However, it was the way I should have gone, and at the end of it I found one of the instructors waiting to receive my message, and to time its receipt. By this time I had lost valuable minutes, and finding on my map that the lane led to a stile and a footpath, I thought I could make up some leeway by crossing the fields to reach a road I was due to take after delivering my first message. At each stile I had to carry the bicycle on my shoulder and then climb over. The day was hot, and I was soon perspiring profusely. Eventually I reached the road I was aiming for, and as I was still behind time, began to peddle as fast as I could, to lessen the margin. Some houses came into view on my right, and as I approached, some children came out from one of them and ran right across the road in front of me. I jammed on my brakes – the wheels stopped going round, and I went over the handlebars, landing on both my arms. There was still no time to lose, and I jumped on the bike again, and delivered the remainder of my messages without further delay.

When I got back I found I had sprained both my wrists in my fall, and I dreaded what would happen the next day, for it was flag sending test at eight words a minute. I had never quite got used to the heavy poles, but hoped the wind would be favourable to keep my flag unfurled. Alas there was no wind of any kind, and I struggled as far as I was able in my agony, to send a readable message to the instructor in the distance. I knew when I had finished I had not succeeded, and I felt that this meant the end of me as far as becoming a signalling instructor was concerned. At the end of the week Capt. Allott read out the results. When he came to my name, he said “L/Cpl. Killikelly failed to pass the flag test. Have you anything to say?” I was able then to tell him of my cycling accident, and he looked at me and said “My boy, you should have told us this before the test was made.” That was all – I was granted my certificate and my failure to pass the flag sending test, ignored. Thus I was relieved to be able to return to Salisbury with the thought that I had at least been successful in every other examination I had taken in Weymouth. The certificate read as follows –

W679-6814 5000 4/16 H W V (P43) G 16/521

A.J. School of Signalling

157-16 Southern Command

Weymouth.

This is to certify that 5579 L/Cpl. J. Killikelly 4th Oxford and Bucks Light

Infantry is qualified to act as 2nd Class Instructor of Signalling in the case of an Officer, or as Assistant Instructor of Signalling in the

case of Non-Commissioned Ranks.

Officer i/c P. B. Allott Capt.

22nd July 1916 Command Signal School. S. C

Salisbury Plain (2).

Shortly after I returned to my battalion, I was given another stripe. I now had flags on both sleeves above the stripes to indicate I was an instructor – previously my flags had been worn only on the left sleeve eight inches above the wrist. Another pleasant change was that I was allowed to share a tent with Sgt. Perkins, though he slept on a camp bed, and I still had to lie on the ground itself.

Stripes had the sad effect of making one’s life rather lonely. Sergeants had their sergeants’ mess, to all intents and purposes an exclusive club, and so kept to themselves. Corporals were not supposed to mix socially with the ordinary private in order to maintain discipline, and thus a corporal seemed to be the friend of no one outside his own little sphere.

I soon found myself very busy giving instruction to new members of the signal section. Polly Perkins was expert in organisation, a very good instructor and lecturer, but he was also very clever in handing over a great deal of the ordinary work to me. Not that I worried very much about that, for I enjoyed my job and liked to be on my own doing it. Mr. Stevenson floated in and out, always the thorough gentleman, never interfering in any way whatsoever.

Before we left the Plain, I had an accident playing football, and the immediate after effects produced on of the few distasteful incidents of my army life. For some reason or other, a scratch team was got together to play a side from a draft shortly to go overseas. I played in my usual position of left half, but Captain Wallace decided he would take the centre forward role instead of his usual one of full back. In the second half, he got tired of his new position, and told me to take his place. Opposing me at centre half was a huge fellow, playing in his new issue of army boots. He wasn’t very good, but strong and clumsy. It came about that I received the ball just in front of him, took it up to him, and then went to take it round him. As I beat him, he swung his right foot at me, and connected with my knee, leaving a gash of some two inches long, and one third of an inch wide. I was carried off the field, at the side of which, fortunately, was an RAMC tent. There I was attended to right away, and my leg bandaged. Finally I reached my tent, and my attendants put me on Polly Perkins bed, and then left me. When Polly came in, he wasn’t at all pleased to see me on his bed, and ordered me off it, so for the rest of the day and the night, I lay in my usual place on the floor. I wasn’t really surprised at Polly’s action, as I had got to know him fairly well by this time, but I never forgot it. Next morning I went on sick parade. This was something that I was not used to, and my only experience had been the day after I had hit my head on the bath bottom at Weston.

I lined up with all the others, and when my turn came, I went in with the medical corporal to the M.O’s tent. I started to tell the M.O. my story, when he stormed at me, and called me all the fool’s names he could think of, for wasting his time when he had so much to do. Of course I should have had the dressing and bandage off, and my trousers down long before I reached him. I took the bandage off, and there was the gaping wound. He hardly looked at it, gave me light duty, and that was that. I found that light duty meant peeling spuds in the cookhouse, so I went to the officers’ quarters, saw Capt. Wallace and told him what had happened. He saw me back to my tent, and I stayed there for the rest of the day. Strangely enough my wound healed quickly – it should have been stitched really – and I have the scar on my leg today to remind me of that happening. I need hardly say that the M.O. of that period was not the same gentlemanly character I had met with in Weston-super-Mare.

There were not many outstanding events on Salisbury Plain that I remember. I seem to recall some small attempts at bayonet fighting and performing extraordinary manoeuvres in battalion formation. On the whole I think I was able to pass the time quietly with the signal section, with whom I got on well. I have mentioned that signallers were excused fatigues, but there were occasions when I was posted as orderly corporal, which meant accompanying the orderly officer on his rounds from early morning until late at night, inspecting tents, cookhouse, meals, and in the evening staying for a short while in the canteen. In those days I didn’t care for the smell of beer, so it was easy to refuse those kind souls who say “Will you have a drink, Corporal?” I was glad, however, that I never had to mount guard, for I was sure I wouldn’t have got away with it.

Leave was very hard to come by during these days on the Plain, for most of the time it was the concern of those who were due to leave for France, and was called embarkation leave. It was quite easy, however, to get a weekend pass, but as this meant paying one’s fare, it was not a great concession, besides which it was not worth while to attempt the awkward journey from the middle of the South of England to Liverpool and back in the short time allowed. I did decide one weekend to pay a visit to my training college in Hammersmith. This wasn’t a great success, for most of my contemporaries had, by this time, joined the army as I had done, and there were few familiar faces left. I was grateful to the Principal for giving me free board and lodging during my stay. One event that occurred during that weekend was the dropping of bombs on the city by a Zeppelin. On the Sunday I paid a visit to see the extent of the damage, and saw a huge hole outside the Adelphi Theatre which had been full on the Saturday night the bomb had fallen. There was only one casualty I believe – a call boy who had been sent on an errand, and left the theatre as the bomb dropped.

Cheltenham.

We left Salisbury Plain without any regrets, and took up Autumn quarters in the pleasant town of Cheltenham. Here we occupied large empty houses, of which there seemed to be a great many in the town. I never discovered why this should be so, even during a war. We found comfort where there had been none on the Plain. Looking back I should imagine that we were spaced about eight to a room, with trestle beds and straw mattresses and three new blankets. Each morning the mattresses were folded back, and the three blankets placed on top showing altogether nine edges. There were a number of open spaces in the town for all kinds of drills and parades, and we signallers were always able to find a quiet spot to carry on with our work. I seem to remember a lot of marching through the streets with my squad, before reaching the parade ground, and there always seemed to be lots and lots of officers to be saluted on the way there.

When we reached Cheltenham we found we had been joined by the Bucks. Battalion of the OBLI. With all the drafts that had been sent to France, numbers had grown less in both battalions, so it was found necessary to bring the Bucks. section into the battalion’s third line. Amongst these Buckinghamshire men were a number of good footballers, and when we joined forces, it was found that we could muster a very fine side between us. Thus began a period of enthusiastic support for the football team which, during the months we stayed in Cheltenham, won every match but one, and that was a draw against an RAF side (editors note: the RAF was not formed until the 1st April 1918 so it would have been a Royal Flying Corps (RFC) side that Jimmy played against) which had previously beaten one of the Bristol League sides.

Each Saturday when we played at home (and this was on most Saturdays) the whole battalion paraded outside Headquarters and, led by the brass band, of which we were very proud, marched to the football ground to see the game. The Colonel and his fellow officers were also there to cheer us on. Capt. Wallace was still in charge, and I retained my place at left half. In front of me at inside left was Lt. Jeffries, who had played for the famous Corinthians, and at outside left was Private Tommy Stevens, who had previously been a Manchester City player. Centre forward was Woodward who had played for Oxford City and at right half, and sometimes at left back L/Cpl Briers – both of these were with me in the Ashcombe Rangers game at Bristol when we took a chance in disobeying the order to remain in billets. Occasionally at right half was a tall chap named Gomm who, after the war, became Millwall’s centre half and represented London in combined team games. The goalkeeper was from Aylesbury United but I cannot remember who formed the right wing.

The centre half, Sergeant Lane, who was from Luton, and I, formed, with Captain Wallace, the selection committee, though as we were a successful side, there was very little change each week unless some regular member was not available. On one occasion Captain Wallace informed us that certain members of the side were due to be sent on a draft overseas, and asked me if I could take a couple in the signal section where they would have three months training to become signallers. Another two were given an intensive musketry course, so that, while we remained in Cheltenham the needs of the BEF (British Expeditionary Force) failed to disturb the composition of the team.

My game was considerably improved playing behind Lieutenant Jeffries and Tommy Stevens, and I thoroughly enjoyed combining with them in attacking football. However it was not long before I was brought to my senses when I received a strong ticking off from Captain Wallace, who told me he was very displeased with the way I was playing. “Remember” he said, “you are an amateur – Stevens is a professional – and I don’t want you to imitate him in all he does. You are there to play for your side, and not try to make a fool of your opponent”. It was a lesson I needed very badly, for no doubt I was getting a swollen head in my attempts to gain applause from the crowds on the touchline. I am glad to say I remembered Capt. Wallace’s rebuke all the rest of my playing career.

The people of Cheltenham, understandably, were not very enthusiastic about having thousands of soldiers in their midst, and we were never encouraged to join in any social gatherings in the town. This attitude is probably reflected in the fact that I cannot remember the church we attended, and it is certainly true to say that no member of the congregation made any friendly advance towards us.

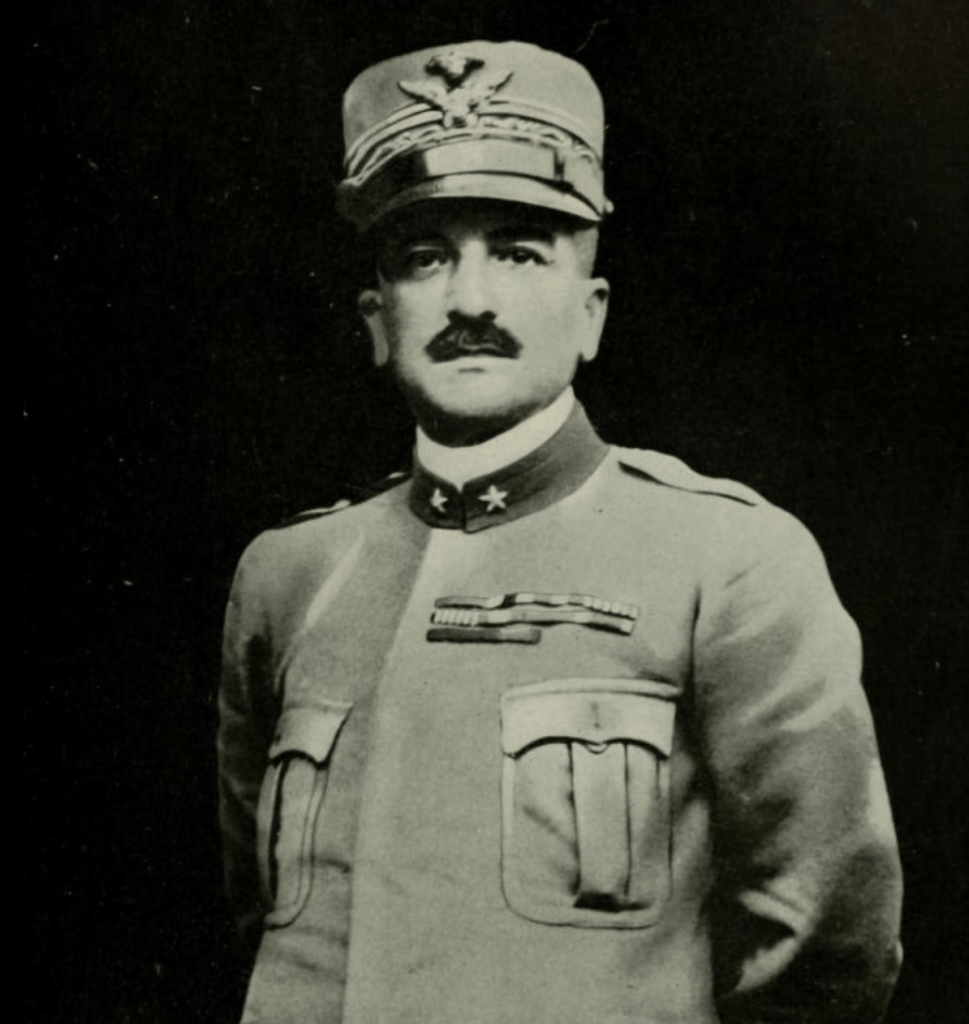

Apart from the football, I always associate Cheltenham with the disastrous march past of the Division through the High Street, when General Plumer took the salute. In order to make sure that everything would go off well, we had a rehearsal of the parade on the day before the General was due to come. Opposite the platform on which the General was to stand, was a combined band of the Warwickshire and Worcestershire regiments. The idea was that there would be a regulation distance between battalions, and as the head of each battalion approached the saluting base, the band would strike up the regimental march past of that particular battalion. Everything went well until we arrived at the spot where the change of march was to be made, and as the 52nd Foot march past began, we knew there was something wrong. The battalion in front of us had marched to the usual pace of 120 to the minute. We dragged our feet, we lengthened our stride, but to no avail – at a moment’s notice we couldn’t come down from 140 to the minute to 120. Thus it was a rather pathetic shambles of the 3/4 OBLI that struggled in vain to present a soldierly smartness as we went past that saluting base.

Field Marshal Herbert Charles Onslow Plumer, 1st Viscount Plumer, GCB, GCMG, GCVO, GBE. 13th March 1857 – 16th July 1932. Editor’s note: Field Marshal Herbert Charles Onslow Plumer, 1st Viscount Plumer, GCB, GCMG, GCVO, GBE (13 March 1857 – 16 July 1932) was a senior British Army officer of the First World War. Affectionately known as ‘Daddy’ Plumer to his men, after commanding V Corps at the Second Battle of Ypres in April 1915, he took command of the Second Army in May 1915 and in June 1917 won an overwhelming victory over the German Army at the Battle of Messines, which started with the simultaneous explosion of a series of mines placed by the Royal Engineers’ tunnelling companies beneath German lines, which created 19 large craters and was described as the loudest explosion in human history. He later served as Commander-in-Chief of the British Army of the Rhine and then as Governor of Malta before becoming High Commissioner of the British Mandate for Palestine in 1925 and retiring in 1928.

When the practice was over, the bandmaster of the combined two regiments was told of the mistake he had made, and was instructed that when the Oxfords reached the position when their march past was to begin, the marching speed would have to be raised from 120 to 140. There was no time for any further rehearsal, and so we hoped for the best.

For some reason or other – I never found out why – signallers always led the battalion on a march. Thus it was that as NCO in charge, I was in front of the signallers and, of course, of the battalion on this memorable march past. It will be noted that, as usual, both Mr. Stevenson and Polly Perkins were cleverly engaged in some other business. Crowds lined the wide High Street as General Plumer took his position on the saluting base, surrounded by officers of varying rank. Ahead of us were the Royal Berks, and as we approached behind them, we could hear the closing strains of their regimental march. There was a slight pause, and the combined bands of Warwicks and Worcesters burst forth once again. We, of course, marched with rifles at the trail, which caused a certain amount of comment amongst the spectators. This soon changed to howls of laughter, for instead of speeding up to 140 paces to the minute, the bandmaster had gone well past this rate, and we were soon racing into the back of the Royal Berks, and double marking time in front of the General. It was estimated by our Regimental Sergeant Major, who was in the crowd, that we had reached the rate of 160 steps to the minute. We could hear, amidst the roars of laughter, shouts of “They’re running, they’re running”. Somehow or other we got past the saluting base, and broke away at the end of the High Street to march at our own pace to our Battalion Headquarters. The RSM summed up our own feelings over the disaster when he went to the Warwick bandmaster after the parade was over, and said, “You only did that because we beat you 8-1 on Saturday.”

Although I enjoyed my football, and taking charge of the routine signal instruction in Cheltenham, I led, on the whole, rather a lonely life, for after Tom Hartney had gone abroad, I had no other particular friend, and often wandered about the town in the evening by myself, before going back to billet and bed. I felt this loneliness most of all at Christmas time when most of the men had gone home on Christmas leave. There were no parades on Christmas Eve, Christmas Day and Boxing Day, and these days dragged on interminably, for no effort was made anywhere to make the season a happy one for the troops.

During our stay in the town, I had an interesting period when I was released by the battalion to attend Divisional Headquarters and examine would be signallers who wished to qualify for their flags. In charge of affairs was Captain Mason, Royal Engineers who had signed my own certificate earlier in the year, and I found him very friendly to work under. My lasting memory of the various tests was of the nervousness of many of the men, much older than I was, whose hands shook as they handled instruments to put them into working order. I wanted to tell them I was only a kindly little fellow, without any harm or guile in me, but that sort of thing wasn’t done. Before leaving Cheltenham, Captain Mason thanked me for who I had done and wrote a pleasing testimonial which I never had the opportunity to use.

Catterick Bridge.

Apart from the football, I had no regrets in leaving Cheltenham. There seemed little cause for the whole division to travel some two hundred miles to the north, especially as the only reason for our being was to send men across to France, whenever there was need to fill up the gaps. We found ourselves, then, in Hipswell Camp early in the New Year, to be greeted with heavy falls of snow, and our main exercise was in keeping the camp paths and roads clear, as soon as the snow stopped falling. Hipswell Camp was close to Catterick, and about four miles away from the historic town of Richmond in Yorkshire. We were billeted in huts, some thirty men to each hut, and again slept in trestle beds lined up in two ranks on each side of the hut. In the centre of the hut was a huge iron stove which kept those fortunate enough to sleep near it, quite warm.

Whenever the weather was suitable we carried on with our signal drill, and flag wagging became quite popular for it kept most of the body comfortably warm. The section was enlarged by the addition of a number of men who had been signallers out in France with the first and second battalions, and who were now pronounced fit for service once again, after being in hospital with wounds or illness. Among these were three NCOs from the 2/4th battalion, one a full corporal, and two lance corporals. The full corporal instantly became unpopular with the rest of the men, and as I was in charge of the hut, I had to see he wasn’t allowed to overstep the mark. One of the newcomers was a signaller from the 1/4th battalion, Reggie Pledge more commonly called Dags – why I don’t know. We were later to become great friends in France, and during the years that followed the war. Another signaller from the 1/4th was named Hammond, and of course went by the nickname of ‘Eggs’. He, too, became a familiar face at the Reunion Dinners in Oxford.

At Catterick we seemed to have more route marches than at previous camps – it may be that the fact I had a significant interest in these, brings them more to mind. I have mentioned previously that the signallers always led the battalion in its travels along the roadside, and as Mr. Stevenson and Sgt. Perkins were always conspicuous by their absence on these parades, it was left to me to guide the battalion on the prescribed route. On the morning of the march Mr. Stevenson would give me a map and show me the course of the march, and then leave the rest to me. At the beginning, all went well – we signallers were supposed to lead at a certain distance ahead of the Colonel, mounted on his horse in front of the band, and leading the four companies. The company commanders, too, were mounted, as were the Adjutant and the Second-in-Command, who usually brought up the rear. Sometimes we would endeavour to be out of sight of the Colonel when the halt was called, and the regiment fell out for a rest at the side of (the) road, for the regulation ten minutes every hour. The Oxfords were unique, I think, in forbidding cigarettes to be smoked on the march, although pipes were allowed. If we could get round a bend of the road at a halt, therefore, we could light a cigarette, and have a pipe at hand in case the Colonel happened to close in on us. To achieve this, we sometimes exceeded the prescribed distance in front of the battalion, and for sometime got away with it. One day, however, he rode up and gave me a ticking off, for marching too quickly.

I was in trouble on some other marches, when the Colonel and I did not see eye to eye. On one occasion, we had to pass through Richmond on the first part of the journey, and I took a turning which was to take us out into the country. The Colonel rode up to tell me I had taken a wrong turning, but I disagreed and referred him to the map – there were alternative means of reaching the main road, and I had chosen one of them. He permitted me to have my own way, and shortly afterwards I was proved to be correct. On the second occasion I came a cropper – I took a side road leaving the road we were on, at a very sharp angle, but when I looked round after travelling a short distance, I saw that the Colonel was leading the battalion along the road we had left. Fortunately for us, there was a gate over which we scrambled into a field, and we raced across this and were lucky enough to find another gate giving access to the road, and allowing us sufficient space between ourselves and the head of the troops, who had, no doubt, enjoyed our discomfort.

My mistake was not forgotten when, on another march, I found our way blocked by a snow drift of several feet. I made my way back to the Colonel, and told him what was ahead. He halted the battalion, and came with me to inspect the condition of the road, and when he realised it was impossible to continue further, he decided to turn the battalion round, and to return to the campy the way we had come. So, we signallers, went back to the head of the line, while they turned in fours in the road to retrace their steps. The whole battalion blamed me for the position they found themselves in, and we were greeted with rude remarks while we made our way past the four companies, a way which seemed interminably long. We were not allowed to forget the mistake I had made on that previous march, and there was no chance to explain the snow drifts we had come across.

One evening, much to my surprise, Polly Perkins invited me to spend a few hours with him in Richmond. We went the four miles or so by obtaining a lift in passing transport, and wandered around that historic town. Before going back to camp we decided to have a drink, and went into one of the inns in the main street. As we passed through the door, we found a number of our own regiment at the bar, and were greeted by the voice of Private Tommy Stevens who welcomed us, and invited us to have one with him. We didn’t wish to get mixed up with the crowd, but didn’t like refusing him, and he bought us a drink. When we had finished we bought him one, and then left him there. Stevens, of course, was the professional footballer, behind whom I had played so many games in Cheltenham, and who had been given a course of signalling to keep him a few months longer in England. When he had a little too much to drink, he was apt to become rather noisy, and a bit of a nuisance, but had not so far got into trouble because of it. We left the pub then, and decided to walk back from Richmond to the camp, and arrived there just before it was time to settle down for the night.

We went to the hut where most of the signallers were, and found the place in an uproar. Tommy Stevens had decided that this was the time that he should tell the corporal, whom most of us disliked, exactly what he thought of him. As things seemed to be going too far, I felt that I, being a footballing friend of Tommy, should try to calm him down, so I went to him and told him to stop his noise and get to bed. To my surprise he turned on me, and went on ranting and raving. By this time Polly Perkins had disappeared, and I concluded he had gone to the sergeants’ quarters. The chaps in the hut asked me to go outside and they would calm Stevens down and get him to bed. I did as they requested and went out into the night air. Snow was still on the ground between the huts and it was decidedly cold. I suffered this for some time, and then I asked myself why I should have to put up with the inconvenience for the sake of a half drunken private. My answer was to walk round to the other door of the hut, and let myself in. As soon as I stepped inside, I saw Stevens still raging up and down the gangway between the beds, and as luck would have it, he, too, spotted me coming in, and rushed to meet me. I decided that on no account would I now give way, and stood my ground as he advanced. I looked at his arms – he was only partially dressed – and noted they seemed as thick as my thighs. He aimed a blow at me which I parried – I had done some boxing at school – but then came a flurry of blows from him, and one got through my defence and nicked me on the nose. As a small amount of blood oozed out from the broken skin, realisation must have come to him that he had struck an NCO, and the boys were able to get hold of him and lead him to his bed, where he fell asleep.

Early morning brought Polly Perkins into the hut, and he told me I would have to put Stevens on a charge. I didn’t want to do this, and said the whole business would better be forgotten. What I did not know was that Polly had been to the guard room, and reported Stevens for being drunk and disorderly in his hut, and the guards were outside waiting to put him under arrest. This they did and I was left to make up my first crime sheet. At company headquarters, the charge was made before the Captain of A Company, when Stevens was accused of being drunk and disorderly and striking an NCO. No evidence was given, for the Captain at once said that the matter was too serious for him to try, and we were told to appear before the Commanding Officer later in the morning. It so happened that the Colonel was away from the battalion at this particular time, and the case was brought before the Second-in-Command. When he heard the evidence of witnesses who had seen what had taken place in the hut the night before, and had listened to my story, and noted the cut on my nose, he, too, said the case was too big for him, and he remanded Tommy Stevens for a District Court Martial.

Tommy was taken back to the guard room and kept under close arrest, and we resumed our ordinary duties, wishing that the whole thing had never happened. Moreover, the RSM, who had been present at the hearing, made both Polly and I feel most uncomfortable, when he forecast that the DCM would probably have us both tried for failing in our duty, in that Stevens should have been put in the guard room immediately he had shown signs of intemperance the night before. Each time we saw him, he kept rubbing this in, and seemed to take delight in the thought of both of us being reduced to the ranks. Whether he was pulling our legs or not, I could not guess, but there was little pleasure to be had during the days that followed.

When these had numbered seven, we learned that the Colonel had returned to the camp, and had decided that the case should be retried. Stevens was given the opportunity to get witnesses for his defence, while I had to call those NCOs in the hut who had been there, to give their version of what had happened. I had to open the trial, and told of what I saw when I returned from Richmond, how I had tried to pacify Stevens, gone out to see if things would quieten down, and then returned to meet a still drunken and angry Stevens, who struck me and cut my nose. My nose had by this time healed, and there was no sign of any blow upon it. The NCOs then told their story, and all of them verified the fact that Stevens had struck me. Sergeant Perkins gave evidence, too, to say that he had reported the matter to the guard room, but didn’t say when, nor did the Colonel ask him, so that particular point which had worried us seemed to be by-passed.

Then came the five privates to give what support they could for Stevens. All of them apparently were busy at the time making their beds, and heard no sounds of quarrelling, nor did they see Private Stevens strike Corporal Killikelly. Tommy, when the last witness had been called, asked the Colonel if he could be permitted to speak on his own behalf. When this was given, he said he had known Corporal Killikelly for some months, and had played football with him, and had always had a friendly feeling for him during that time, and the last thing he would have dreamt of doing, would be to strike him. In fact he had met both Sergeant Perkins and Corporal Killikelly in a public house in Richmond that same night, and all had drinks together.

At this, the Colonel sat up – it was the first time it had been mentioned. “Oh”, said the Colonel, looking at me, “It seems to me that you were all drunk. I have listened to this charge very carefully, and have come to the conclusion that there is too much conflicting evidence – the case is dismissed.” There was relief on all sides at his verdict, and we all marched out feeling the sky was bright again. An amusing sequel came a couple of days later, when we played our only inter-battalion match at Catterick. As usual, the Colonel was present with his staff on the touch line – there came a moment when play took place in front of him – I had the ball and Tommy Stevens called for it, “right Jimmy!” I passed the ball to him with “here you are Tommy”, as as the ball sped to him, I looked up to see the Colonel wiping a smile of his face with his gloved hand, and the thought went through my mind ‘The Wisdom of Solomon’.

I have referred to the lack of Christian Charity in the dealings of the members of the various Catholic Churches I had attended, but here in Catterick, I met some of those truly religious people who spend their time doing good for others. A mile or so away from our camp was a wooden building erected and maintained by the Catholic Women’s’ League. On Sunday mornings we few Catholics in the battalion would march to Mass there preceded by a Scottish Highlander playing his bag-pipes. Bag-pipes were never, nor have been since, my favourite musical instruments, but I realised why the Scottish battalions always seemed to march with that majestic swing, whenever we chanced to meet them on the road. It was a great pleasure to march each Sunday behind that lone Scottish Highlander.

After Mass, those soldiers who had been to Holy Communion, were invited by these kind ladies of the CWL to sit down to a beautifully cooked breakfast, for otherwise we should have had to remain fasting until our midday meal. This breakfast was something we did really appreciate. The hut served both as a church and as a recreation centre, for the altar and sacristy were shut off after the service by means of sliding screens. During the week soldiers of all creeds used the room for reading, playing games, and sometimes for concert parties. My last memory of this church was on the day I was due to set off overseas. There was an early Mass each day, so I decided to go to Confession and Holy Communion before I started on my journey to join the British Expeditionary Force. It happened that I was the only person present and the priest asked me if I could serve Mass. It was with delight then that I joined him at the altar to make the responses for the first time since I was an altar boy.

It had been obvious for some time that there would be a large number sent out from Catterick because of the losses sustained by the first and second lines in the Battle of the Somme. Although I was not particularly anxious to get killed, I felt that I would hate, in after years, to think that I had joined the army, and not experienced the full life and dangers of a front line soldier. So when I knew that I was due to leave the peaceful surroundings of Hipswell Camp, to join those members of the OBLI who had survived the miseries and hardships in France, there was a certain amount of satisfaction in knowing that if I came through it all, I could hold my head up high, and know that I had taken my share with those who had gone out there before me.

I regretted leaving Mr. Stevenson who had done such a lot to make my association with the third line signallers as enjoyable as it could be. I never heard of him again – apparently he didn’t go abroad as he was not fit for trench duty – and I often wondered if he returned after the war was over to his professorship amongst the gleaming spires of Oxford. He wrote the following testimonial for me before we parted, but like the one I received from Captain Mason, I never had any opportunity to make use of it.

“Corporal James Killikelly has done excellent work as an instructor in

signalling in this battalion during the last six months. He has enjoyed

a very good education, and found no difficulty in understanding and

explaining to others the more difficult parts of e.g. electrical theory.

In spite of his youth he was able to exercise authority, and was much

respected by the men. I hope that, when he goes to France, he may

find opportunities to use his knowledge and experience.”

G.H. Stevenson Lt.

Signalling Officer

Res. Batt. 4th Oxf. Bucks L.I.

Hipswell Camp, Yorkshire.

And so, after five days embarkation leave, I found myself one day on the station at Darlington waiting for the troop train which was to take us to London. On our arrival there we had to wait some hours before going on to Southampton, and were given permission to spend that time looking round the capital. I was asked by one of the signallers, who were part of the draft, to go with him to see his relations. This little excursion passed the time pleasantly and we both enjoyed the meal that we sat down to there.

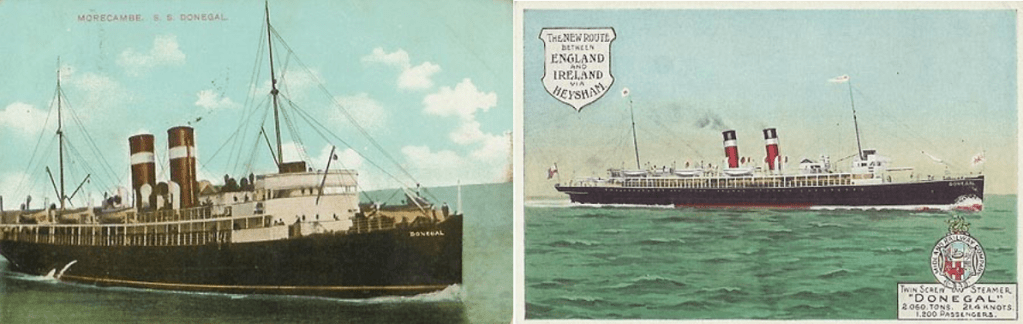

We came into Southampton Docks Station at dusk and boarded a troopship named ‘Donegal’. There were, I imagine, some 1500 of us on board, and in the dark night air we set off for Le Havre which meant a much longer trip than Dover to Calais of Folkestone to Boulogne.

Postcard of the SS Donegal Part Two.

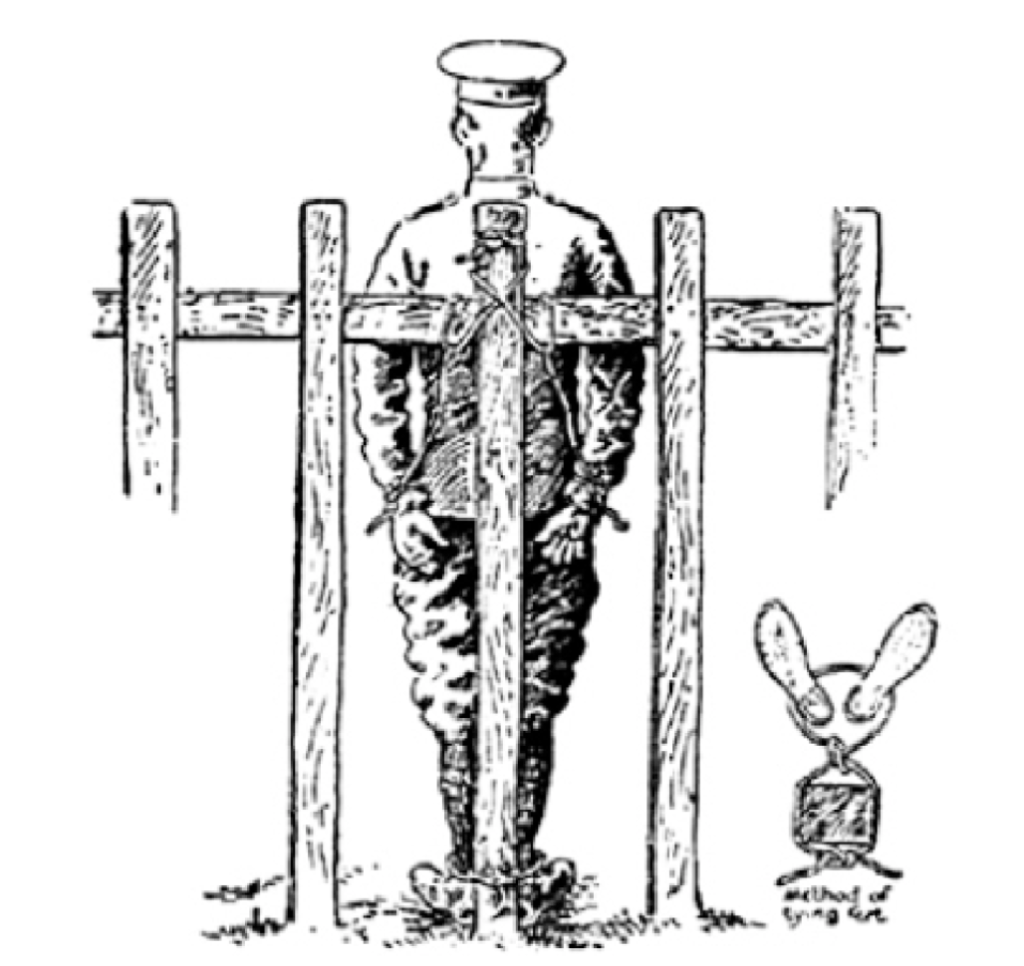

France (Le Havre and Rouen).